The

problematic value of a handknit sweater plays into the most famous of

all knitting urban legends, “the boyfriend sweater curse.” The story

goes if you knit your boyfriend a sweater it will end your relationship,

either by the process of knitting it, or by the boyfriend’s

insufficient love of the sweater when finished. Books such as Judith

Durant’s Never Knit Your Man a Sweater (Unless You've Got the Ring),

organize their whole premise around the curse. Other publications

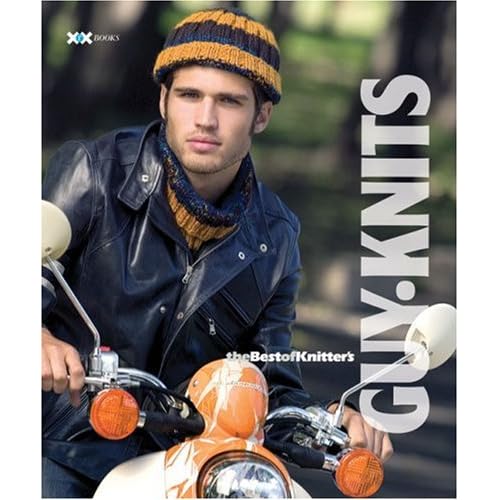

mention the curse in their introductions. Guy Knits, a book of patterns

for men to wear, bosts this introduction,

The

problematic value of a handknit sweater plays into the most famous of

all knitting urban legends, “the boyfriend sweater curse.” The story

goes if you knit your boyfriend a sweater it will end your relationship,

either by the process of knitting it, or by the boyfriend’s

insufficient love of the sweater when finished. Books such as Judith

Durant’s Never Knit Your Man a Sweater (Unless You've Got the Ring),

organize their whole premise around the curse. Other publications

mention the curse in their introductions. Guy Knits, a book of patterns

for men to wear, bosts this introduction,

“Men who knit are still in the minority, but guys love knits--let's not neglect them. When we knit for a guy, it usually means that the knitter is not the wearer. So we need to understand what the guy is comfortable wearing. Do this, and you needn't worry about that old boyfriend-sweater curse. As always, knit with love, but make sure that love is not blind. After all, handknits should enhance, not complicate, a relationship.”

As a book full of patterns for men, the book assures the reader that these patterns are so excellent they are in no danger of the curse.

The introduction to Guy Knits also brings up an interesting question of

gendered language. Although the introduction admits only a “minority” of

male knitters, and that “usually “ they are not knitting for

themselves, the author assumes that the reader, and therefore the

knitter, is a woman. When publications do recognize the possibility of

knitting men, the writers often congratulate those men for being man

enough to knit with titles like Knitting with Balls. The tone of these congratulations often implies that

knitting is something men need courage to undertake. Which is strange because although knitting is a

female-dominated field, but it is also a powerless one, and one that men

can enter if they happen to be interested in knitting, but they would

have no other incentive to do so.

The introduction to Guy Knits also brings up an interesting question of

gendered language. Although the introduction admits only a “minority” of

male knitters, and that “usually “ they are not knitting for

themselves, the author assumes that the reader, and therefore the

knitter, is a woman. When publications do recognize the possibility of

knitting men, the writers often congratulate those men for being man

enough to knit with titles like Knitting with Balls. The tone of these congratulations often implies that

knitting is something men need courage to undertake. Which is strange because although knitting is a

female-dominated field, but it is also a powerless one, and one that men

can enter if they happen to be interested in knitting, but they would

have no other incentive to do so.All of this is a big messy issue, but one which is close to my heart for several reasons. One is that my boyfriend is a knitter and a good one. He knits lace and cables, writes and designs his own patterns, he's even had a pattern he designed published in Interweave Knits, a widely recognized knitting magazine. When I tell people that my boyfriend knits most people are both very surprised and very impressed. I think people are impressed for two reasons: for one, I think people are impressed that he thinks something which is usually considered a female craft (at least at this point in history) is worth learning. They are impressed that he is interested in knitting as a craft, and interested enough to learn how to do it. The second reason people are impressed is because he knits astoundingly well. Not just because he chooses (or creates) really beautiful patterns, or because he uses very high quality materials, but he knits very evenly and carefully with an admirable attention to all the details of weaving in loose ends, and fixing all the mistakes he makes along the way.

He doesn't just knit. He knits really well. And this is the reason I think all of our crafting is worthwhile. Even if none of us make money on Etsy. Even if Linden and I have spent hundreds of hours doing craftwork for All's Well, this work is important not just because our work has given value to those objects and costume pieces, but because our work has given value to ourselves. We have and are building some really exciting skills. Both of us have been learning a lot through the experience by learning new skills. We've both become much more creative and capable with paper as well as with fabric. Learning from Jenny McNee of the American Shakespeare Center has been lovely in part because she is a good teacher and a good sounding board for our ideas, but also because she is incredibly skilled. She knows how to make fabric do incredible things. I think that skill itself is a thing of value, worth learning, worth possessing in oneself and worth preserving for the future.

He doesn't just knit. He knits really well. And this is the reason I think all of our crafting is worthwhile. Even if none of us make money on Etsy. Even if Linden and I have spent hundreds of hours doing craftwork for All's Well, this work is important not just because our work has given value to those objects and costume pieces, but because our work has given value to ourselves. We have and are building some really exciting skills. Both of us have been learning a lot through the experience by learning new skills. We've both become much more creative and capable with paper as well as with fabric. Learning from Jenny McNee of the American Shakespeare Center has been lovely in part because she is a good teacher and a good sounding board for our ideas, but also because she is incredibly skilled. She knows how to make fabric do incredible things. I think that skill itself is a thing of value, worth learning, worth possessing in oneself and worth preserving for the future.

and does not write her own story. She has more soliloquies than most of Shakespeare's heroines--she is certainly trying to tell her own story in a way so few female characters get to. But at the same time, once she has married Bertram, she must play by his rules--she must fulfill the story he creates when he writes the letter.

and does not write her own story. She has more soliloquies than most of Shakespeare's heroines--she is certainly trying to tell her own story in a way so few female characters get to. But at the same time, once she has married Bertram, she must play by his rules--she must fulfill the story he creates when he writes the letter.