a work in progress to share ideas and inspirations as we prepare for a feminist fairytale production of Shakespeare's play.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Blank Paper and Luxurious Textiles

“Innogen’s own language picks up on the extent to which textiles have become metonymic of her body when Pisanio shows her the letter in which Posthumus orders her murdered for her infidelity. But Innogen envisions herself as a completely worked garment rather than the blank sheet of chastity on which a man might write. Before she begs Pisanio to carry out her husband’s order, she castigates herself for having lost Posthumus’s faith in her, calling herself “a garment out of fashion,” which, too “rich” to be translated into a wall hanging, must be reduced to rags: “And, for I am richer than to hang by th’ walls,/ I must be ripp’d:--to pieces with me!” (3.4.50-53). As a garment too elaborately made--too complete in its own identity to be cut up and translated into a wall hanging--Innogen must be ritually destroyed, ripped to pieces. To Giacomo, she may be the blank white of the sheet, but Innogen sees herself in terms of luxurious, colorful textiles, even as she imagines herself as that rich cloth ripped to pieces” (186).

In this project we’re looking at ways of re-defining the “blank page” of femininity, and it is exciting to see that redefinition happening as the texts are being written. What other characters use textiles as metaphors for themselves? Or for other characters? And what does it say about them?

Friday, November 4, 2011

Notes from the Director: All's Well, Fairytales, and Gender

I think, in the midst of the lovely work Clara has done and continues to do, it is time that I chime in about my end of this project. When Clara first had the idea for a pop-up book production, I spent days considering what play would suit the medium—what play would be right for such a fairytale aesthetic.

Eventually, I settled on All’s Well That Ends Well. For me, pop-up books conjure images of story time, of the fairytales I spent my childhood immersed in. My love for these stories has resurfaced in recent years when I discovered the delights of The Decameron and was fortunate enough to stumble across Andrew Lang’s beautifully-illustrated series of books, each named for a different colored fairy.

And I see All’s Well as just such a fairytale—but, somewhat unusually, with a female protagonist. So many fairytales feature a male hero who undergoes a series of trials only to be rewarded with a beautiful princess to marry. In this case, however, the hero is a woman—a woman pursuing a lover herself. And this shift is where some of the trouble seems to begin.

I was in a class this morning where the problem of the All’s Well’s ending came up in a review of a production of the play. The reviewer, Bernice Kliman, described the problem of the play in the form of a question: “what on earth does Helena—a fine woman, as Shakespeare’s text insists—admired by all right-thinking characters, see in that callow youth, Bertram?” Our professor insisted that the real problem was why everyone was so willing to attack Bertram for refusing to marry a woman he didn’t love. And I think this criticism is fair—Bertram does not begin this play as a villain; he cannot help that he does not love Helena. But in fairytales, this never seems to be a problem. The princess is simply never asked—no one cares whether she loves or does not love the hero. So why do we care so much if Bertram does? Why does the play make a problem of this?

And it is this that excites me about All’s Well—the way the questions of gender and marriage coincide without easy solution. The way the play uses and challenges the structures of fairytales. With the beautiful work Clara has done, considering paper in its early modern relationship with gender and modern relationship with digital media, I am excited to begin exploring this play in production.

Images by H. J. Ford

Thursday, November 3, 2011

Some Academics

Objective for this Directed Inquiry:

To research and construct all elements of design for our production of All’s Well that Ends Well, paying particular attention to the construction of the set, costumes and props as signifiers creating meaning along with the words and bodies of the actors.

Things we need to accomplish in this DI:

Design and make the set

--Research the images/sketch out what we want to make

--Research how to make it

----Research the construction of popups

----Research the construction of large pop-ups

Design and make the costumes

--Find out what we have to work with

--Decide what else we need to do

----Alter the clothing/sew costumes

----Design and construct all paper pieces of the costumes

Design and make the props

--Figure out what they are

--Design and make all the props

Design the poster

Design the programs

Other things:

Reading the play-searching for images/props

Word searches: paper, letter, book

Researching Folklore

Researching folklore and Shakespeare

Researching fairytale imagery

Possible schedule:

Week one:

Re-read the play for images and props. Do word searches in the play. Go to the public library read fairytales, look at pop-up books-- draw pictures of ideas and things we like best. Write blog post.

Week two:

Research folklore and Shakespeare. Write blog post.

Week three:

Research pop-up construction. Design and construct a possibility of set design. Write blog post.

Week four:

Make sure we have all the cast’s measurements. Brainstorm about costumes, determine what have already with wits and with old laundry, etc. Sketch some ideas. Write blog post.

Week five:

Hit up all the thrift stores, procure patterns for any costumes we plan on building from scratch and go to Valley fabrics to get some materials. Write blog post.

Week six:

Make a plan for how the costumes are going to be constructed, who is helping, which tasks to tackle first, etc. Fill in the next three weeks with very specific details of task delegation. Write blog post.

Week seven:

Work costumes. Write blog post.

Week eight:

Work costumes. Write blog post.

Week nine:

Work costumes. Write blog post.

Week ten:

Research all the props and determine what they are and will need to be. Make a plan for all the props, and get started on them. Write blog post.

Week eleven:

Complete the rest of the props. Write blog post.

Week twelve:

Design the poster and program. Research the construction of extra large pop-ups. Write blog post.

Week thirteen:

Construct the pop-up set. Write blog post.

Week fourteen:

Construct the pop-up set. Write blog post.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Lavatch and Clowns in Art and Shakespeare

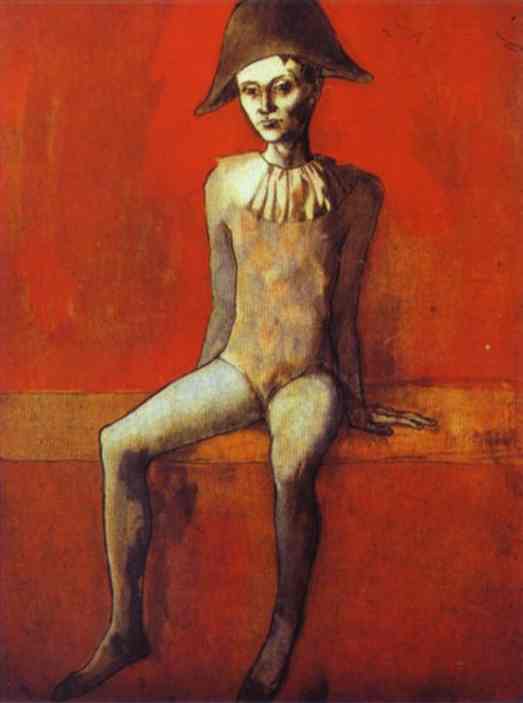

In All's Well, the fool is named Levatch, and he's a bit of a curious character, sometimes overshadowed by the boisterous Paroles. The Globe education website gives some lovely interviews from their recent production of All's Well, including two with Colin Hurley the actor playing Lavatch. Here is the link to the first, and the second interviews. Do enjoy. Also, here are some Picasso harlequins, circus performers and just sad clowns. I imagine we'll use some of these ideas in costuming Levatch, and possibly Paroles as well.

Monday, October 3, 2011

Pottermore and books

The visuals for the intro video to J. K. Rowling's newest adventure combine some fascinating ideas about books as they transition between tactile and digital forms. The animated books, cut and shaped into moving sculpture show paper texts as malleable through digitization. Who knows how many websites sport Potter fan fiction right now, but J. K. Rowling is taking the her readers' writing under her own wings. As she says, "Just as the experience of reading requires the imaginations of the author and the reader to work together to create the story, so Pottermore will be built in part by you, the reader."

What does this mean for books in the future? Many scholars have explored the expansive possibilities of digital texts, hypelinked footnotes, the kindle's dictionary on demand, comparative texts from different printings and editions made simple through the use of technology, but Pottermore seems to be something entirely new. Something part fan club, part DVD-special features, part video game, and part storylab.

The intro video with its movable books is a perfect introduction to such a phenomenon. Part nostalgia, part magic, part exhibition of technologies in action.

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

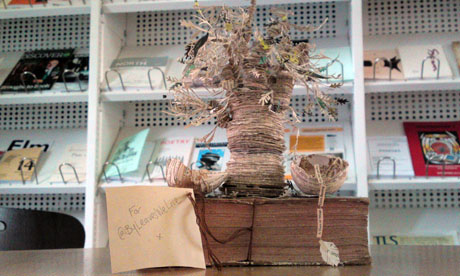

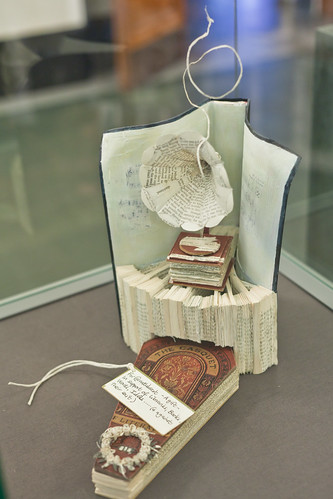

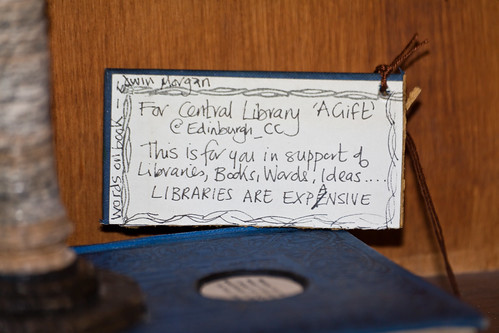

Mysteries in Scotland

The Scottish Poetry Library has recently received an anonymous gift. A paper sculture of a tree, made all out of books. The Guardian is charmed but doesn't know what to think

Grand Central details the story as more sculptures appear, in an outpouring of love for books and for libraries.

These sculptures seem to be coming from one, exuberant lover of books and libraries. Although I love much of the progress towards digitized media, (this blog I'm writing is one I could not share without digitized text), I am sorry for the libraries. And what better way to celebrate the love of libraries than with artwork celebrating the paperness of books now.

Thursday, September 8, 2011

The Ice Book

The Ice Book (HD) from Davy and Kristin McGuire on Vimeo.

While looking into paper sets and pop-up books as sets Linden came upon this short film advertising for a miniature show made of pop-ups and light design. We're not going to turn the lights out on our audience in All's Well, but Davy and Kristen McGuire, the artists behind The Ice Book use the lights masterfully. For more information about their show read the information packet about their show, or go to their website.

What does a set made of paper contribute to this show? Is it just the delicacy? The portability of little theater? The translucence? Is there something about books coming to life that is itself magical?

Tuesday, September 6, 2011

Playing Paper

My understanding of fairytales comes from storybooks. Hardcover, full-color beautifully designed books that send their messages through pages with decorated capitals and a font chosen to suggest manuscript. Books that evoke a tradition, a past, a notion that even if Paul O. Zelinsky’s Rapunzel was published in 2002, tells its story as though it belongs in a time beyond regular dates, far away and long ago. That message of the fairytale is one which seems to belong in paper, but also in performance, where the symbols which soak each page of a fairytale are easily recognizable onstage. We know the young girl, starry eyed and full of wonder, chasing after her dreams. We know the young prince seeking to find his place in the world, and we see the forces around them, be they magical or political or comical bringing them together or tearing them apart. They are characters which resist electronic transfer. What would the text of Harry Potter be without the the font designed for J. K. Rowling, morphed out of design or layout into the convenience of an ebook? It would still be the same words, but the aura of fantasy would be altered, and not merely altered but reduced.

When performing a play cast with fairytale characters, it seems most natural to return to books and to paper as the operating medium for the symbols those characters so richly possess. For All's Well that Ends Well, the cinderella story with the prince-not-so-charming, Linden Kueck is working ideas of fairytale to comment on ways in which stories are passed down from generation to generation, and how human beings, but particularly women color their actions to conform to the cultural stories they believe they should be a part of. To facilitate this goal, I will be working as her designer to build a set, props, and even some costume pieces out of paper. All the paper will be white, and at least in this point in the process we are imagining the paper clean and unwritten on, the blankness of a common metaphor for women, as the object on which men inscribe. The white paper also serves as a symbol which will work to emphasize the texture of the paper, and with no color to distract, except for any symbols of power (the crown, the ring) set off in a startling red.

You might wonder, if the set is to be a book made of blank paper, where is the artistry of design so looked for in a fairytale? Since first coming in contact with electronic books, I have been exploring the ways in which the tactile properties of paper affects the understanding of a story. This often true in picture books where much of the drama of the story lies in the turn of the page as a codex, something which would be lost if viewed on a screen unless the program simulated the turn of the page in some sort of graphic medium. I have already mentioned books published in a specific font which would loose some of their charm if morphed into the regular typeface of an ebook. But of all kinds of books, the type most resistant to digital translation is the pop-up book. I find it vastly amusing to see the “Tell the Publisher! I’d like to read this book on Kindle” link on Amazon for Robert Sabuda’s Movable Mother Goose, because pop-up books or movable books in general glory in the paperness of paper, and explore all of its creative potential. White Noise, a popup book by David A. Carter explores the different sounds that paper makes through a series of abstract pop-up spreads united through a poem. Others use cut shapes to show the figures they portray without any printing onto the shapes. Still others revisit often told tales and make them live by giving them a third dimension. Pop-up books seem especially pertinent at the particular point in history, as we, like the Early Modern culture are in a time of textual transition. Culture in England was moving from manuscript to print, and culture today is moving from print to digital, our times are mirrored in a way, and that mirroring deserves some comment, comment made by books which revel in their paperness.

But what can all this fascination with paper and stories lend to a rehearsal room? Would it merely give us a heightened awareness of the lines pertaining to paper and print? To the paper props? The letters? (Are they blank? If not, what’s written on them?) How does an historical awareness affect a production? Will the pop-up book set feature castles --slightly postmodern in their architecture? What if the posters were cut paper? Pop-up programs? What would that say about the production? Simply that paper is important? That it should be noticed and valued for the story it tells in itself, not only what is imprinted on it?

In this way, the paper itself can be a metaphor revisited. If early modern writers objectified women by using images of books and paper which are meaningless without a male hand composing their significance, playing with paper dismantles that binary. Paper can convey meaning through its own folds, a meaning without words but expressively augmenting the actions and words of the actors on the stage, presenting their stories with a backdrop of tradition and fantasy. Whose tradition and whose fantasy is up to the audience to unfold.

Intro post

So who am I and what am I doing this project for?

My name is Clara Giebel and I am designing for a production of William Shakespeare's All's Well that Ends Well as directed by Linden Kueck. This project is in partial fulfillment of our Master of Fine Arts degree in Shakespeare and Performance. Looking particularly at what in this play is like a fairy tale I am working to give this production a distinctly tactile, papery visual aura, one which draws the audience's attention to the characters and also to our place in the history of books and paper industries.

Why All's Well?

All's Well that Ends Well provokes questions with its very title. As a story of a woman in love with a man who cares nothing for her, and ultimately coerces him into joining her an accepting marriage, the audience is often left wondering if all has ended well. The two young people are together at the end, but is that good for either of them? In a "talkback" with the actors after a recent production at the American Shakespeare Center, the actors playing this couple were asked point-blank if they thought it would work out, and the actors didn't have a straight answer. Helena's all in, but is that enough? These aren't questions that have clear answers, which opens up many doors to a variety and richness of interpretation.

Why this blog?

Linden and I will be using this blog to post information we are thinking about, images and media which play into our explorations of this play and the concepts we are playing with. There will be some scholarly writing, lots of pictures, photographs of the set, props and costumes in progress, and a lot of opportunity for discussion.

Image from Jackie Huang.